Some data from NCSC should be helpful in relating access to justice strategy to overall legal system changes.

This is because this data simply blows away the way we think about the courts.

The dominant analytic mode has always been that cases involving self-represented litigants are the exception in state civil courts, deserving of special educational programs for judges, perhaps a self-help center and online forms, and, in a really progressive state, even some form of assistance in the courtroom.

Well and good. But now we not only know, but have the data to show that it is all completely inside out.

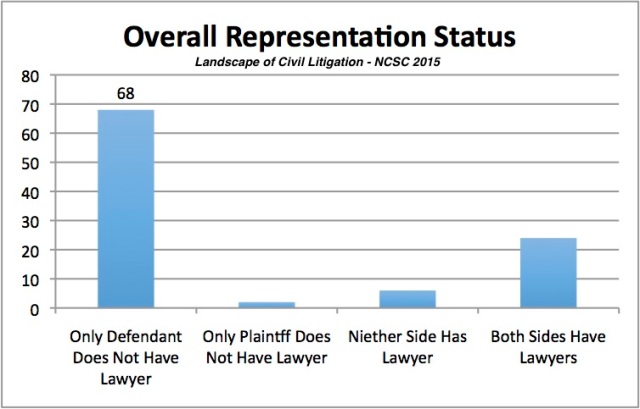

Last year, NCSC’s Civil Justice Project issued its Landscape of Civil Litigation of State Courts, and this data has been made use of in the chart on page 11 of the Project’s Call to Action. The chart shows percentages of plaintiff represented, defendant represented, and both represented in a variety of situations and contexts.

I have played with the percentages data, which comes from ten urban counties, randomly selected from counties that had participated in prior such studies. The list and analysis is at page 14-15 of the Landscape. Over 650,000 cases for which full representation status data was reported are included. The only civil cases not included in the data collection are those described as “domestic” (Landscape at iii) This is a critical fact for self-represented litigant analysis, and likely leads to significant under-inclusion of cases with no lawyer on both sides in the number.

So, at the general level, this is the Civil Court “Scope of the Problem” chart.

At a minimum, this chart shows that the problem, in civil court at least, is far more the cases with only one side having a lawyer (70%), than the very different problem of the situation of where neither side has a lawyer, and that these cases swamp both-sides- represented cases. In contrast to our world view, the one-side represented situation is the modal one, and heavily so. As the Landscape Report Executive Summary puts it: “At least one party was self-represented (usually the defendant) in more than three-quarters of the cases.”

What a shattering change to the self-image of courts this requires, and what a challenge to access to justice, and what a rethink of our whole court management, indeed whole civil justice system, challenge.

Given the total mismatch between the design assumption that almost everyone has a lawyer, and the reality shown by these numbers, its hard not to think that this is the core of all courts’ problems, and that other issues, like funding, delay, prestige, and private sector alternatives, are a directly or indirectly the product of this underlying force.

Among the immediate system design implications.

- Clerks offices are now much less important than self-help centers. It is not even clear that clerk’s offices should exist. Probably they should be absorbed into self-help services.

- Judicial education should be completely restructured, with the majority of courtroom training components focusing on cases with one self-represented litigant.

- Judicial selection should be changed to ensure that we get judges with the right skills, and that those who think they want to be judges know what they are signing up for. An unhappy judge is a bad judge.

- Technology projects, and particularly e-filing, should be built so that they work as well for the self-represented as they do for lawyers.

- Every court, and almost every court committee, needs individuals and senior managers with a primary focus on self-represented cases.

- Rules should assume that the dominant mode of cases is the dominant mode.

- Caseflow management must be focused on those who need help, rather than attorneys. No wonder it fails now.

Thanks so much to NCSC for the very hard work of bringing this data together (we know how hard it is) and making it accessible.

More to come in future posts on the more detailed data, and its potential use in access to justice strategic planning.

A short note on methodology — let me know if you find a hole. NCSC very kindly send me the percentages in the representation chart in the Landscape report in a spreadsheet, and I just played with them. The full sample represents about 5% of cases nationally, and the cases with representation data involve a bit more than two thirds of that.

-

The “plaintiff only represented” percentage is derived by subtracting “both represented” from “plaintiff represented.”

-

Similarly for “defendant only represented.”

-

“Both represented” comes directly from the chart itself.

-

Then “other than both sides represented” is derived from subtracting “both side represented” from 100%.

-

Similarly, “Either only plaintiff represented or either only defendant represented” is derived by adding “only plaintiff represented” and “only defendant represented.”

-

Finally, “no representation for either side is derived by subtracting “either only plaintiff represented or either only defendant represented” from “other than both sides represented.”

Richard, this corroborated the article in the NCSC Future Trends in State Courts 2016, by Hannah Lieberman and Paula Hannaford-Agor (page 89). Meeting the Challenges of High Volume Civil Dockets.

In this paper they ID challenges with high volume dockets that need attention: inadequate service, confussing chaotic court rooms, inadequate pleading, insufficient litigant information, hallway settlements, litigation pitfalls and suggest solutions: improve process service and other notifications, require adequate pleadings remote access, control conduct of attorneys in the courthouse, language access, judicial training.

My favorite ones are: eliminate inadequate pleading, if inadequate pleadings were not filed, we would not have “zombie debt cases” for example. It would reduce the number of cases and thus the number of defendants going to court alone to challenge something they don’t know how to challenge and do something they don’t know how to do, demurrers, motions for summary judgement and the like. Plus it would not stain a person’s credit record for ever. Lots of good would come out of this. Remote access–b/c I know not everyone lives in the 10-20 sq mile area near the court house, and that for a lot of people getting there is hard. Unlike pharmacies or hospitals courts are not as evenly distributed as they need to be. So remote access and satelite locations (remote self help centers) are a great way to bring the courts to the people, not the people to the courts. And of course, language access. With out quality interpretation, there will be no meaningful participation–and the decisions are at high risk of getting something wrong or not being understood, forcing the case back to court, over and over again. Best to get it right the first time and get an order that works for all.

Thanks for sharing.

Pingback: We Now Have Data To Help Prioritize ATJ Strategic Focuses | Richard Zorza's Access to Justice Blog

Pingback: We Now Have Data To Help Prioritize ATJ Strategic Focuses | Richard Zorza's Access to Justice Blog